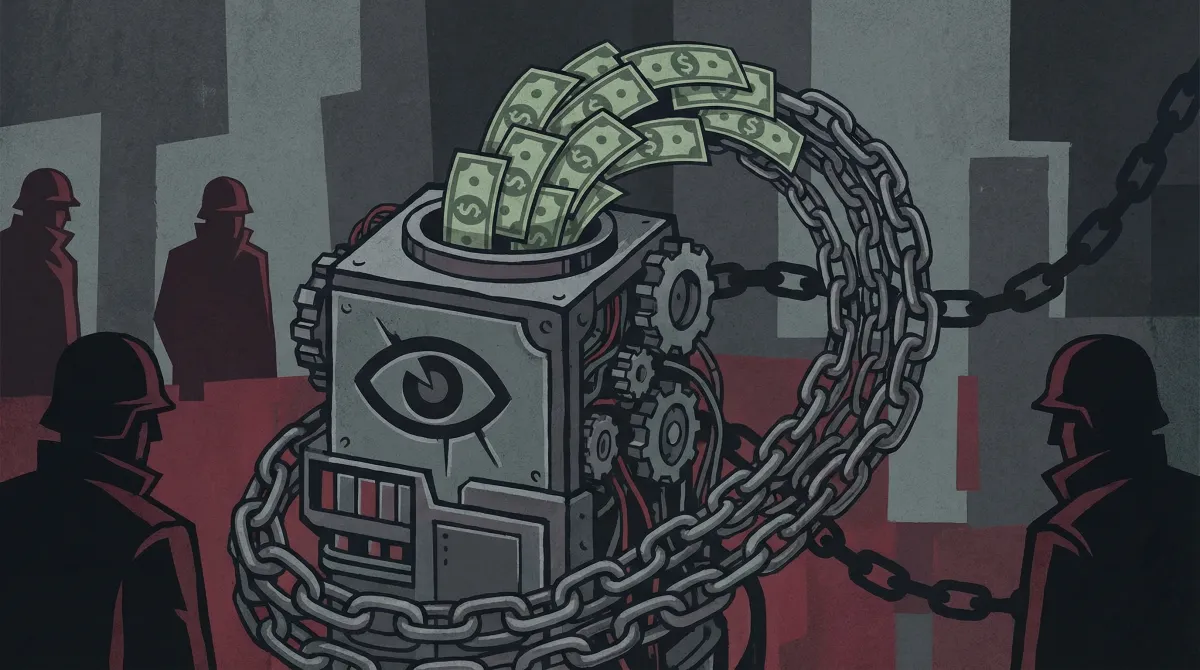

Are We Buying Into Authoritarianism?

The keyword:

INFRASTRUCTURE.

Seventy-three percent of people currently held in ICE detention have no criminal conviction.

Not "violent criminal conviction." No criminal conviction at all.

This single statistic, verified by the Cato Institute using TRAC Immigration data, should reframe everything you think you know about Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

The Conventional View

The standard pitch for 287(g) agreements goes something like this: Local law enforcement knows their communities. When they identify someone here illegally who's also committing crimes, they should be able to coordinate with federal authorities rather than releasing dangerous people back onto the streets. These are voluntary partnerships that make communities safer.

It sounds reasonable. It sounds like common sense.

But it misses what's actually happening.

Follow the Money

On September 2, 2025, the Department of Homeland Security announced a dramatic expansion of financial incentives for local law enforcement agencies to partner with ICE. Starting October 1, 2025, participating agencies receive:

- Full salary and benefits reimbursement for each trained 287(g) officer

- Overtime coverage up to 25% of annual salary

- Quarterly performance bonuses — $1,000, $750, or $500 per officer — tied to "successful location" rates

- Early signup bonuses: $7,500 for equipment per officer, $100,000 for new vehicles per agreement

Read that again. Performance bonuses based on finding immigrants.

This isn't a public safety program. This is a bounty system.

And the results are predictable. The share of ICE detainees without any criminal conviction or charge has exploded from 6% to 40% between January and November 2025. Of new detainees added during the government shutdown, 97% had no criminal history whatsoever.

When you pay for bodies, you get bodies. Whether they're criminals becomes irrelevant to the incentive structure.

The Private Prison Pipeline

The federal government isn't the only player writing checks.

GEO Group and CoreCivic, the two largest private prison operators in the United States, hold a combined market cap of $6.2 billion. GEO derives 43% of its revenue from ICE contracts. Both companies donated $2.8 million to the Trump 2024 campaign and inaugural fund.

The day after the 2024 election, GEO stock jumped 41%. CoreCivic rose 29%.

This isn't speculation about motives. It's financial reporting. These companies exist to fill beds, and 287(g) agreements are the pipeline that fills them.

With $45 billion allocated for new detention centers and 287(g) agreements having grown from 135 to over 1,300 in a single year, the infrastructure being built is substantial. Jobs are being created. Budgets are being established. Contractors are being hired.

The question isn't whether this infrastructure exists. The question is: once built, how does it dismantle itself?

Historical Precedents

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

Federal law requiring local enforcement against a targeted population isn't new.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required state and local officials to assist in capturing escaped slaves. It penalized officials who refused to cooperate with fines of $1,000. Commissioners who heard cases received $10 if they ruled the person was a fugitive — and only $5 if they ruled otherwise.

Sound familiar? Different payouts based on the desired outcome.

The response was also familiar. Vermont passed a law offering habeas corpus to detained fugitives and requiring state attorneys to intervene on their behalf. President Fillmore threatened to send the Army. Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin all passed personal liberty laws forbidding state officials from cooperating.

In 1855, the Wisconsin Supreme Court declared the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional — the only state court ever to do so. The state went further, paying the legal costs of anyone prosecuted under the federal law and forbidding property seizures to collect civil judgments.

By 1860, only about 330 enslaved people had been successfully returned to Southern masters. The law was virtually unenforceable in Northern states.

The parallel isn't perfect, but the pattern is instructive: federal government conscripts local authorities to enforce policy against a specific population. Financial incentives corrupt the system. Resistance emerges at the state level.

Japanese Internment

The same legal authority being invoked for today's immigration enforcement — the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 — was used to justify Japanese internment during World War II.

Local police assisted FBI raids beginning December 7, 1941. Executive Order 9066 authorized "assistance of state and local agencies" in what became the forced relocation of 120,000 people, most of them American citizens.

Justice Robert Jackson's dissent in Korematsu warned that the principle of emergency detention "lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need."

Infrastructure built for one emergency becomes permanent. The weapon stays loaded.

The Trust Collapse

Beyond the moral and constitutional questions, there's a practical problem: 287(g) programs make everyone less safe.

A University of Illinois study found that 4 in 10 Latinos became less likely to report crimes when local police enforced immigration law. In Prince William County, Virginia, research found that "Hispanic opinions on police plunged to unprecedented lows" after 287(g) implementation.

A Dallas study demonstrated the inverse: when immigration enforcement was reduced, crime reporting increased by 4%.

This isn't counterintuitive. When calling 911 might get your family member deported, you stop calling. Domestic violence goes unreported. Witnesses to crimes stay silent. The entire information network that community policing depends on breaks down.

And it's not just immigrants who become less safe. When witnesses don't cooperate, criminals of all backgrounds operate with greater impunity. The communities where these programs operate become more dangerous, not less.

The Infrastructure Warning

Here's what keeps me up at night: this infrastructure doesn't undo itself.

Consider what's been built in just one year:

- 1,372 memoranda of agreement across 40 states

- 8,501 trained task force officers, with 2,000+ more in training

- Performance-based compensation systems with quarterly reviews

- New vehicles, equipment, and operational budgets

- Private prison contracts locked in for years

- Career paths and institutional knowledge

And then Congress made it permanent. The "One Big Beautiful Bill," signed July 4, 2025, allocated $85 billion to ICE — more than all other federal law enforcement agencies combined, and exceeding the entire Justice Department's budget request.

Every one of these creates stakeholders with a vested interest in continuation. Sheriffs whose budgets now depend on ICE reimbursements. Officers whose overtime pay comes from immigration enforcement. Private companies whose shareholders expect returns. Suppliers who've won contracts. Construction workers building detention facilities.

Texas has already mandated that every sheriff in a county with a jail must apply for 287(g) by December 2026. All 67 of Florida's sheriff's departments have signed agreements. The infrastructure is becoming law.

When the next administration takes office — whoever that is, whenever that is — what leverage will they have to dismantle any of this? The budgets are set. The jobs exist. The contracts are signed. The political constituencies are organized.

And here's the darker question: what happens when the federal money runs out? The supplement funding expires. The performance bonuses end. But the infrastructure remains — the trained officers, the detention beds, the contracts, the careers built around enforcement. All of it looking for a reason to continue existing.

Infrastructure built for one purpose rarely gets repurposed. It usually just finds new populations to process. It usually just finds new populations to process.

What "Ideal" Would Actually Look Like

If the goal were actually public safety, the system would look entirely different:

- Resources would flow to community policing, not bounty hunting

- Success metrics would measure trust and crime reporting rates, not location percentages

- Immigration enforcement would be separated from local law enforcement to preserve cooperative relationships

- Detention would be reserved for those who pose genuine safety risks, not the 73% with no criminal history

But that's not where the money is flowing. And money shapes systems more reliably than rhetoric does.

The Question We Should Be Asking

The standard debate asks: "Should local cops enforce immigration law?"

That's the wrong question.

The right question is: "What infrastructure are we building, who profits from it, and what happens when the next person decides to point it somewhere else?"

Because 287(g) isn't really about immigration. It's about building a system that pays local authorities to identify and detain targeted populations — with financial incentives that corrupt the mission, private profits that demand continuation, and an expanding apparatus that won't dismantle itself.

We've built this kind of infrastructure before. We know how it ends.

The question is whether we'll recognize it this time before the weapon is fully loaded.

Sources: TRAC Immigration, Cato Institute, DHS, Brennan Center, American Immigration Council, Governing.com