Part 2 — The Structural Problem: Why Private Prisons Can't Be Fixed

The problems with CoreCivic aren't about bad management—they're built into the business model. Here's why privatizing human detention creates incentives no amount of oversight can fix.

In Part 1, we examined CoreCivic's operations, contracts, and track record. The picture wasn't pretty: preventable deaths, forced labor allegations, facilities operating despite federal closure recommendations, and a revolving door between government and corporate boardrooms.

But here's the critical question: Are these problems fixable with better oversight? Or are they inevitable consequences of privatizing human detention?

The answer matters. If CoreCivic's problems stem from poor management, we can fix them with stricter contracts and better monitoring. If they stem from the structure of privatization itself, no amount of oversight will work—the incentives are too deeply misaligned.

This is a structural analysis of what happens when you introduce profit motives into human confinement.

The Nine Structural Failures

1. Democratic Accountability Collapses

The Problem: Private corporations aren't subject to the accountability mechanisms that govern public agencies.

What This Means in Practice:

When a federal prison fails, citizens can:

- File FOIA requests to see internal documents

- Demand congressional hearings with subpoena power

- Vote out elected officials who oversee the agency

- Organize public testimony at appropriations hearings

When a CoreCivic facility fails, citizens face:

- Proprietary business information shields operations from FOIA

- Company executives aren't subject to congressional subpoena (unless criminality is suspected)

- No electoral accountability—shareholders vote, not citizens

- Limited public input into contract terms (negotiated behind closed doors)

The CoreCivic Evidence:

The Torrance County Detention Facility received a rare "management alert" from the DHS Inspector General in 2022 calling for immediate closure. The facility continued operating. Why? Because the contract terms allowed it, and neither citizens nor Congress could compel CoreCivic to act beyond contract minimums.

A public facility under similar scrutiny would face congressional hearings, budget pressure, and potential leadership removal. CoreCivic faced a stock analyst question on an earnings call.

The Structural Reality: You can't vote out a CEO. You can't FOIA a corporation. Democracy requires transparency and accountability—privatization eliminates both.

2. The Revolving Door Buys Access and Influence

The Problem: Former government officials move to corporate boards, bringing insider knowledge and relationships.

CoreCivic's Board:

- Stacia Hylton — Former Director, U.S. Marshals Service (2010-2015)

- Harley Lappin — Former Director, Federal Bureau of Prisons (2003-2011)

- Thurgood Marshall Jr. — Former Cabinet Secretary under Clinton

What They Bring:

- Procurement knowledge — Understanding of how contracts are awarded, what criteria matter, how to structure winning bids

- Relationship capital — Personal connections with current officials who were former colleagues

- Institutional insight — Knowledge of agency culture, regulatory weak points, enforcement priorities

- Legitimacy laundering — Respected former public servants provide a veneer of propriety

The Conflict:

When Stacia Hylton sits on CoreCivic's board while the company bids for U.S. Marshals Service contracts, several things happen:

- Her former colleagues at USMS may be evaluating those bids

- Her knowledge of USMS procurement is now corporate property

- Her presence signals to agency staff that CoreCivic is an "insider"

- Public interest and corporate interest become indistinguishable

This isn't illegal. It's also not fixable through better contracts—the knowledge and relationships already transferred.

The Structural Reality: Regulatory capture isn't a bug; it's how the system evolved. Former officials are valuable precisely because they know how to navigate the regulations they used to enforce.

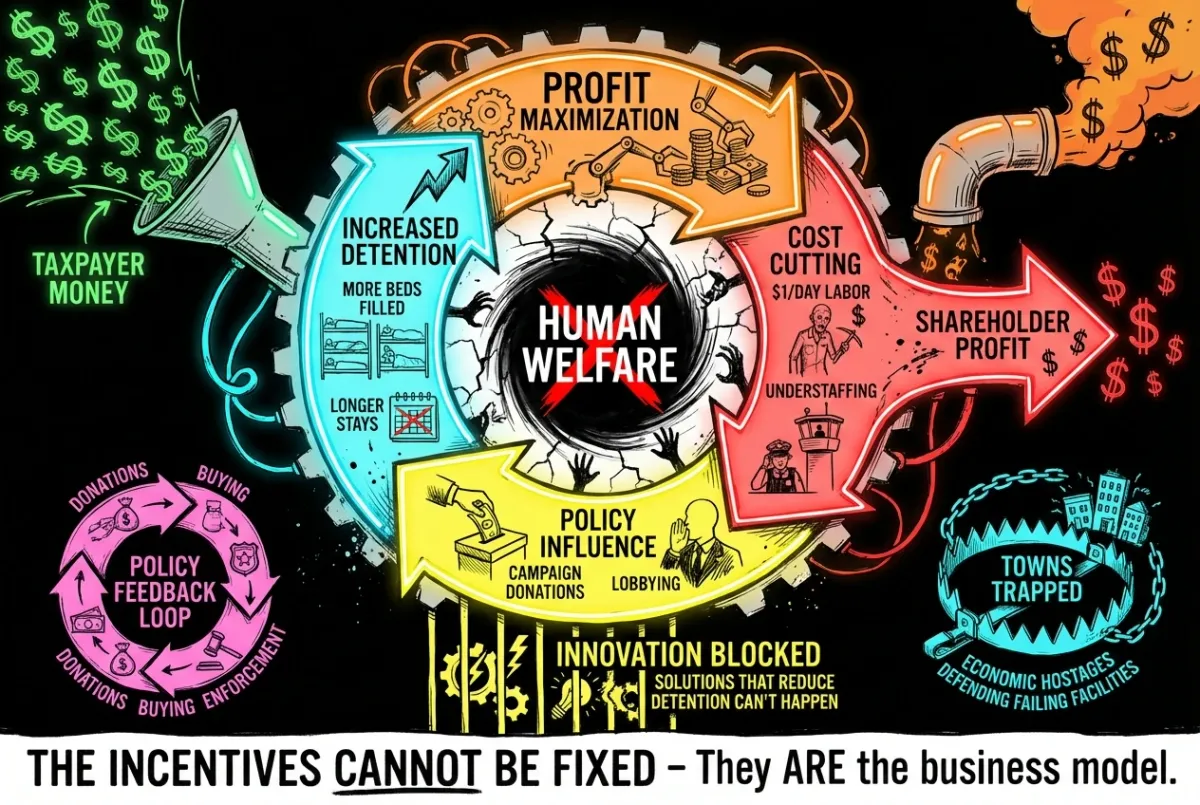

3. Profit Motive and Human Welfare Are Structurally Opposed

The Business Model:

CoreCivic generates revenue through:

- Daily per diem payments for each detainee (higher occupancy = higher revenue)

- Guaranteed minimum contracts (taxpayers pay even for empty beds)

- Cost minimization (lower operational costs = higher profit margins)

The Math:

- Revenue driver: More people detained for longer periods

- Profit driver: Spending less per detainee

- Shareholder return: Maximizing the gap between revenue and costs

The Structural Conflict:

Every dollar saved on:

- Mental health staffing

- Medical care quality

- Recreational programming

- Educational services

- Facility maintenance

...is a dollar earned for shareholders.

The Evidence:

- Kesley Vial (23, Brazilian asylum seeker) died by suicide at Torrance County after staff ignored mental health warning signs. The lawsuit alleges chronic understaffing was the cause. Understaffing is a cost-saving measure.

- Forced labor lawsuit alleges detainees performed janitorial work for $1/day or faced solitary confinement. Using detainee labor instead of hiring fair-wage workers is a cost-saving measure.

- Torrance County conditions (unsanitary living, security lapses, critical staffing shortages) persisted for years. Each of these failures saved money.

The Question: If your fiduciary duty is to maximize returns to shareholders, and every improvement in detainee welfare costs money, what do you optimize for?

The Structural Reality: A corporation that prioritizes detainee welfare over profit is violating its fiduciary duty to shareholders. The incentive structure requires cost-cutting on human dignity.

4. Economic Dependency Trap Creates Structural Complicity

The Pattern:

- Struggling rural town accepts CoreCivic facility for economic relief

- Facility becomes the town's largest employer

- Local economy becomes structurally dependent on detention revenue

- Performance problems emerge at facility

- Town officials defend the facility (economic survival requires it)

- Objective oversight becomes impossible

- Federal intervention recommended

- Town warns of "economic ruin" if facility closes

- Facility continues operating despite failures

Case Study: Torrance County, New Mexico

The DHS Inspector General recommended immediate closure in 2022. The facility had:

- Critical staffing shortages

- Unsanitary living conditions

- Security lapses endangering detainees

County officials warned that closure would cause "economic ruin." The prison was the county's largest employer. Officials who should have been overseeing the facility became its defenders—not because conditions were acceptable, but because their local economy couldn't survive without it.

The facility stayed open. A 2025 Civil Rights Commission follow-up found conditions "hadn't meaningfully improved."

Case Study: Mason, Tennessee

Population: ~1,000 Choice: Accept CoreCivic facility or risk insolvency

Mayor Eddie Noeman championed the project:

- $325,000 in annual property taxes

- 240 new jobs

Over 150 residents protested. They asked: Will locals actually get those jobs, or will managers commute from Memphis? Will the town be able to diversify its economy, or will the prison crowd out other industries?

The city council voted to proceed. They had no real choice—the town needed the revenue.

The Research:

Academic studies on prison towns show consistent patterns:

- Crowding out: Prisons deter other industries due to stigma

- Leakage: Economic benefits are lower than projected because higher-paid staff live elsewhere

- Volatility: When facilities close, local economies collapse

The Structural Reality: Once a community becomes economically dependent on detention, it loses the ability to provide objective oversight. The economic survival imperative overrides the accountability imperative.

5. The Innovation Paradox: Success Requires Failure

The Business Question: What happens if we succeed at rehabilitating people? What happens if we reduce recidivism? What happens if we process asylum claims faster?

The Business Answer: Revenue decreases.

CoreCivic's business model is structurally opposed to every genuine innovation in criminal justice and immigration enforcement:

| Innovation | Impact on Detention | Impact on Revenue |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic monitoring | Reduces need for beds | ↓ Revenue |

| Community supervision | Reduces need for beds | ↓ Revenue |

| Faster asylum processing | Reduces detention duration | ↓ Revenue |

| Alternative sentencing | Reduces need for beds | ↓ Revenue |

| Rehabilitation programs that work | Reduces recidivism/re-detention | ↓ Revenue |

The Political Implications:

CoreCivic states publicly that it doesn't lobby for laws determining the basis for incarceration—like sentencing guidelines or immigration enforcement levels.

But in December 2024, the company's PAC donated $500,000 to pro-Trump causes ahead of the inauguration. Trump campaigned on mass deportations and strict immigration enforcement. More enforcement = more detention = more revenue.

In Q1 2025, CoreCivic lobbied on DHS and Bureau of Prisons appropriations. When H.R. 1 allocated $45 billion for detention through 2029, CoreCivic's stock price surged.

The company doesn't lobby for strict enforcement officially. But it financially supports candidates who promise it, and it lobbies for the appropriations to fund it.

The Feedback Loop:

Strict enforcement → More detention → Higher revenue → Campaign donations →

Candidates promising strict enforcement → Strict enforcement...

The Structural Reality: A company whose success depends on high detention rates will never genuinely support policies that reduce detention—even if they claim neutrality. The incentives are too powerful.

6. Quality Control Fails Because Failure Is Profitable

The Public Sector Model:

When a federal prison fails to meet standards:

- Agency reputation suffers

- Congressional oversight increases

- Budget scrutiny intensifies

- Leadership faces consequences

- Workers (career civil servants) have incentive to report problems

The Private Sector Model:

When a CoreCivic facility fails to meet standards:

- Company faces potential contract loss (but other contracts continue)

- Stock analysts ask one question on an earnings call

- Contract terms often allow continued operation if minimums are met

- Leadership faces consequences only if revenue drops

- Workers fear job loss if facility closes, creating pressure to hide problems

The Evidence:

The Torrance County facility operated for three years after the Inspector General's management alert. Why?

- Contract terms allowed it

- No mechanism existed to compel immediate closure

- County officials defended it (economic dependency)

- CoreCivic faced no meaningful financial penalty

In a public facility, bipartisan outrage and congressional pressure would force immediate action. In a private facility, the contract defines the obligation—and public outrage has no enforcement mechanism.

The Death Toll:

Between 2022 and 2025, multiple preventable deaths occurred at CoreCivic facilities:

- Kesley Vial (suicide, Torrance County)

- Abelardo Avellaneda Delgado (death in transit, TransCor)

- Jesus Molina-Veya (suicide, Stewart Detention Center)

Each death should trigger investigation, accountability, and system-wide changes. Instead, operations continued. Why? Because the contract was still profitable, and profitability—not safety—is the measure of success.

The Structural Reality: In a profit-driven model, failure is only meaningful if it affects revenue. Preventable deaths, unsanitary conditions, and understaffing only matter if they risk contract loss. Until then, addressing them is a cost that reduces profit margins.

7. The Forced Labor Business Model

The Lawsuit Allegation:

CoreCivic detained people were forced to perform janitorial work—cleaning common areas, not just their own cells—for $1 per day or sometimes no pay at all. Refusal could result in solitary confinement.

CoreCivic calls this a "Voluntary Work Program." Plaintiffs call it forced labor under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act.

The Financial Stakes:

The lawsuit has been certified as a nationwide class action. If CoreCivic loses:

- Billions in back-pay damages for unpaid or underpaid labor

- Elimination of the cost-saving measure the industry relies on

- Fundamental restructuring of the business model

Why It Matters:

Using detainee labor for $1/day instead of hiring workers at market wages is a core part of the profit model. It's not an aberration—it's how operational costs are kept low enough to generate returns.

If CoreCivic is forced to pay market wages for janitorial, maintenance, and food service work currently performed by detainees, profit margins collapse.

The Structural Reality: The business model depends on exploiting a captive labor force that has no exit option and no bargaining power. This isn't a bug to be fixed—it's the feature that makes the model profitable.

8. Political Influence Creates Feedback Loops

CoreCivic's Influence Operation:

Federal Lobbying (Q1 2025):

- Appropriations for Department of Homeland Security

- Appropriations for Bureau of Prisons

- "Fair Access to Banking Act" (penalize banks that refuse to lend to private prisons)

Political Contributions:

- $500,000 PAC donation to pro-Trump causes (December 2024)

- Ongoing state-level contributions to candidates supporting strict enforcement

ALEC Ties:

- American Legislative Exchange Council (where corporations and state legislators draft model legislation)

- Privatization-friendly bills and stricter sentencing guidelines

The Feedback Loop:

Campaign donations → Candidates promise strict enforcement →

Candidates win → Strict enforcement policies → Increased detention →

Higher revenue → More campaign donations...

The Policy Capture:

When the company's revenue depends on policy outcomes, "lobbying appropriations" becomes lobbying for more detention funding. When financial support flows to candidates promising mass deportations, that's indirect lobbying for policies that drive detention rates.

The company isn't neutral on policy—its financial interests are policy preferences.

The Structural Reality: You can't separate corporate financial interest from policy advocacy when revenue depends on specific policy outcomes. Private prisons will always exert influence toward policies that increase detention, regardless of public statements about neutrality.

9. Transparency and Accountability Are Structurally Incompatible

What Citizens Can't Access:

- Internal incident reports

- Staffing levels and qualifications

- Medical care protocols

- Solitary confinement usage data

- Real-time facility conditions

- Contract negotiation terms

- Performance incentive structures

Why They Can't Access It:

"Proprietary business information" shields operations from public scrutiny. FOIA doesn't apply. Congressional oversight is limited to what contracts require reporting.

The Contrast:

Federal Bureau of Prisons facilities operate under:

- FOIA requirements

- Congressional oversight

- Inspector General audits

- Public budget transparency

- Media access (limited but exists)

CoreCivic facilities operate under:

- Contract terms (negotiated privately)

- Proprietary business secrecy

- Shareholder interest (not public interest)

- Limited external oversight

The Evidence:

We only know about Torrance County's failures because the Inspector General conducted an investigation. We only know about the forced labor allegations because detainees filed a lawsuit. We only know about specific deaths because families demanded investigations.

How much don't we know?

The Structural Reality: Privatization adds a layer of opacity on top of an already opaque institution (prisons). The result is accountability squared—even less transparency than the deliberately secretive public system.

The Core Question: Can This Be Fixed?

Supporters of private prisons argue that better contracts, stricter oversight, and stronger penalties can solve these problems.

Let's examine that claim.

What Better Contracts Would Require:

- Real-time public reporting of all incidents, staffing levels, medical outcomes

- Immediate termination clauses for safety violations (no cure period)

- Independent inspections with unannounced access and subpoena power

- FOIA-equivalent access to all operational documents

- Penalty structures that exceed the profit from violations

- Prohibition of forced or underpaid labor

- Guaranteed minimum abolition (pay only for actual occupancy)

- Ban on political contributions and lobbying by contractors

What Would Happen:

If those contract terms existed, private prisons would stop bidding. The profit margins would disappear. The entire business model depends on:

- Cost-cutting that compromises care

- Guaranteed minimums that eliminate occupancy risk

- Limited transparency that prevents public accountability

- Political influence that shapes enforcement policy

Remove those advantages, and there's no reason to privatize—the supposed "efficiency" gains vanish.

The Fundamental Tension:

CoreCivic is a corporation with a fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder returns. In this business, that means maximizing detention while minimizing cost per detainee.

No contract can align that incentive with humane treatment. The structure itself is the problem.

What This Means for Policy

If You Support Private Detention:

These structural problems must be acknowledged and addressed:

- End guaranteed minimums — Pay only for occupancy

- Require FOIA-equivalent transparency — Eliminate proprietary shields

- Ban political contributions and lobbying by detention contractors

- Create immediate termination authority for safety violations

- Mandate independent oversight with subpoena power

- Eliminate forced or underpaid labor

- Prohibit revolving door between detention contractors and government agencies

If these reforms make private detention unprofitable, that reveals the business model depended on the very problems it claims not to have.

If You Oppose Private Detention:

The structural analysis strengthens the case:

- The problems aren't fixable with better management—they're inherent to the model

- Oversight can't work when economic dependency creates complicity

- Accountability fails when transparency is proprietary

- Innovation is blocked when success reduces revenue

- Quality control fails when failure is profitable if it doesn't violate contract minimums

The solution is ending privatization of human detention—not improving it.

The Path Forward

CoreCivic is entering what may be its "golden age" of profitability. The $45 billion in detention funding through 2029 represents unprecedented revenue opportunity.

But a "golden age" for CoreCivic means:

- Record numbers of humans in detention

- Prolonged confinement durations

- Continued cost pressures on care and staffing

- Persistent structural conflicts between profit and welfare

When CoreCivic's stock price surges, that means beds are full.

The debate over private prisons will continue. But it should be informed by structural analysis, not anecdotes. The question isn't whether CoreCivic is well-managed. The question is whether any corporation can align profit incentives with humane treatment of human beings.

The evidence suggests the answer is no—not because of individual failures, but because the structure of privatization creates incentives that no amount of oversight can overcome.

What You Can Do

Research:

- How does your state use private detention?

- What oversight mechanisms exist?

- What are the contract terms?

Advocacy:

- Support transparency requirements

- Demand FOIA-equivalent access to private facility data

- Push for ending guaranteed minimum contracts

- Advocate for banning political contributions by detention contractors

Electoral:

- Ask candidates about private detention policy

- Research campaign contributions from CoreCivic and GEO Group

- Support candidates committed to ending privatization of human confinement

The structural problems with private prisons are solvable—but the solution is ending privatization, not perfecting it.

This is Part 2 of our CoreCivic investigation. Part 1: Your Tax Dollars at Work examined the company's operations, contracts, and track record.

What structural problems do you see in other privatized government services? Where else does profit conflict with public interest?